A new acquaintance from my fencing salle in Singapore, reading my

post about some teenaged foilists eyeing my sabre, and was surprised to see that I called them, users of Pistol (or anatomical) grip, wimps. He was also surprised that I said I preferred French grip to Pistol grip and Italian to both. He was under the impression that the Pistol grip was proven to have better point control.

I pointed out that while the Pistol grip makes basic point control easier for beginners, it tends to encourage a death-grip situation where one ends up controlling the point with wrist and arm movements, not at all conducive to subtle fencing, which should be about skill and speed, not brute strength.

I have a penchant for things Italian - I address my fencing teacher in Singapore as

'Maestro', whereas everyone else seems to call him merely

'Coach'. I quote from

Maestro William Gaugler:

---

The argument favoring the Italian grip and wrist strap was succinctly put by Maestro Nadi in his book,

On Fencing, published in 1943. On page 44 he wrote:

Its outstanding advantage lies in (the Italian foil’s) superior power. The handle is bound to the wrist by a leather strap…which insures a strength and firmness of grip…More important, it lightens the burden of the fingers, thus permitting most of their effort to be employed in directing the point (offense). Furthermore, the strap increases effectively the power of the parry (defense).Maestro Nadi’s lessons embodied everything that was characteristic of traditional Italian fencing: efficiency, speed, and mobility. He demanded extraordinarily tight point control, a light touch, firm command over the opposing steel, rapid execution, and dynamic attacks accomplished with a step or jump forward. Above all, he stressed economy of motion.

How different Aldo Nadi’s fencing was from the wild and inelegant swordplay we are confronted with today. Maitre Leon Bertrand, on page 119 of his book,

Cut and Thrust, published in 1927, quotes the celebrated Italian master, Candido Sassone, as saying “that the attack should succeed eight times out of ten.” In the recent Olympic Games at Los Angeles it was not uncommon for a fencer to make three or four attempts before a touch was scored. And more often than not, the hits arrived by chance. With the fencers twisting and turning, effecting acrobatic contortions, and rushing together to jam their weapons into one another, all vestiges of organized fencing disappeared; nearly every movement seemed to be improvised on the strip.

That there exists a relationship between the style of weapon and school is inescapable. The design of the arm favors the execution of particular actions, and prompts a specific tactile approach. In this respect, the French school provides an excellent example. Until the latter part of the 17th century there was little difference between the Italian and French schools. The crucial factor in the separation seems to have then the introduction of a practice weapon without the crossbar. An early version of this may be seen in Labat’s text,

L’art en fait D’armes, published in 1696. The straight handle permitted good point control, but was not well suited to effecting actions on the blade.

By the beginning of the 19th century the French foil was fitted with a figure-eight shaped guard, and required a large padded glove to protect the armed hand. With the stuffed glove actions on the blade necessitating sensitivity of touch became a problem, so French masters placed stress on actions such as the cut-over which avoided blade contact. Expulsions and transports, though still in the repertoire of movements, were relegated to a secondary position. Emphasis on separation of parry and riposte may also have resulted from use of a weapon without a ricasso or crossbar, since it would tend to be less sensitive to blade contact. Opposition parries linked with gliding ripostes, as commonly practiced in the old Italian school, could not have been as easily effected with the French foil. Even today, with the modern French bell guard and abolition of the padded glove, French masters often show a predilection for actions without blade contact, and are prone to adopting a defensive rather than an offensive posture. The relationship of grip and school in France can be traced in La Boessiere,

Traite de l’art des armes (Paris: 1818); Louis-Justin Lafaugere;

Traite de l’art de faire des armes (Lyon: 1820); Cordelois,

Lecons d’armes (Paris: 1862); Camille Prevost,

Theorie practique de l’escrime (Paris: 1818); and Georges Robert,

La science des armes (Paris: 1900).

The same bond between weapon and school prevails in Italy where fencers, regardless of the type of grip they employ, favor a form of swordplay that is derived from their traditional weapon. Certainly, no 17th- or 18th-century Italian swordsman would have felt secure in a duelling situation if he could not sense his adversary’s blade; and a riposte accomplished by releasing the parried steel would have been regarded as sheer folly. In similar fashion, contemporary Italian fencers continue to work along the blade when possible, and to rely heavily on offensive movements.

Radaelli is said to have summarized the Italian tactical approach by stating that the parry does not exist; in other words, if the offense is correctly executed, there is no defense.It would appear then, despite talk of an international school, that there still are distinct Italian and French schools, and that these are closely tied to their traditional weapons.

The orthopedic grip, popular largely since the advent of electrical foil fencing, is used by fencers of both schools, and has been adapted to suit the peculiarities of each of the systems. But it has also deprived swordsmen of the advantages that the traditional arms have to offer in point control and sensitivity. And these are unquestionably major factors in fencing safety.

With the Italian and French weapons greater precision and delicacy of touch are possible. If thrusts are executed in the orthodox manner using either of these arms, the hand is generally in supination and the sword arm fully extended, so that the point fixes firmly on the target and the blade bends consistently in the same direction.

By insisting on use of the Italian foil grip in its examinations, the Council of the National Academy of Fencing at Naples has taken the first step toward a return to classical fencing; in other words, efficient, elegant, and safe swordplay.

Italian leader Silvio Berlusconi has published a book of insults thrown at him by the left-wing opposition. Berlusconi ti odio (I hate you Berlusconi) is an apparent attempt by the PM to show his critics in a bad light, correspondents say.

Italian leader Silvio Berlusconi has published a book of insults thrown at him by the left-wing opposition. Berlusconi ti odio (I hate you Berlusconi) is an apparent attempt by the PM to show his critics in a bad light, correspondents say. A set of ancient silverware has been dug up from Pompeii, the Roman city destroyed by a volcano 2,000 years ago. The hand-crafted goblets, plates and trays had been bundled into a wicker basket by an inhabitant fleeing the erupting Mount Vesuvius in AD 79.

A set of ancient silverware has been dug up from Pompeii, the Roman city destroyed by a volcano 2,000 years ago. The hand-crafted goblets, plates and trays had been bundled into a wicker basket by an inhabitant fleeing the erupting Mount Vesuvius in AD 79.

ROME, JULY 17, 2005 (Zenit.org).-

ROME, JULY 17, 2005 (Zenit.org).-

The Travel Yup likes exotic and adventurous travel, but prefers big cities with fast paced life. He has a keen interest in other cultures and always brings home a few souvenirs.

The Travel Yup likes exotic and adventurous travel, but prefers big cities with fast paced life. He has a keen interest in other cultures and always brings home a few souvenirs.

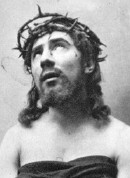

In 1909, Bela Lugosi played the role of Jesus Christ in a theatrical Passion Play.

In 1909, Bela Lugosi played the role of Jesus Christ in a theatrical Passion Play.

The Road to Jerusalem

The Road to Jerusalem The Knight Templar

The Knight Templar